Illusions of grandeur

11.04.2003

Illusions of grandeur

Dr. Christoph Müller

Veröffentlicht auf LinkedIn am 11.04.2003

Competition in Germany is in its fifth year, and according to what statistics you look at, it has been a phenomenal success. A glance through the company reports of Germany's major electricity companies will reveal that competition has unleashed a flurry of activity. Some companies have achieved remarkable growth in sales volumes, up to six times their sales when they were monopolies.

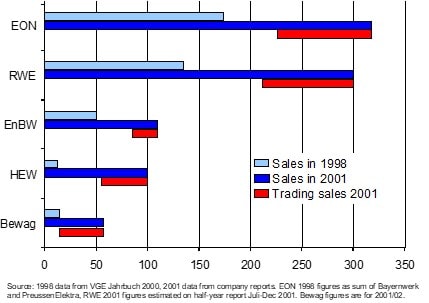

The figures are remarkable. Eon, taking the combined supply volume of its predecessors, has grown from supplying roughly 175TWh to around 330TWh. RWE has gone from 135TWh to around 300TWh; EnBW from 49TWh to 110TWh. Small German electricity companies have also recorded high growth: HEW, part of Vattenfall Europe, sold about 14TWh in 1998. It now supplies 100.9TWh. MVV, the municipal supplier for the town of Mannheim, has grown from 1.5TWh to 14TWh.

Growth figures of such magnitude would be surprising by themselves. However, they are doubly so because in terms of physical switching, the German market has not been very dynamic: only about 5 per cent of all customers have changed supplier. Neither has the market itself grown dramatically, since total demand in Germany has grown at only a moderate rate.

So what is going on? In a word: trading. While there have always been bulk sales to other retailers in the German market, in recent years sales by trading have become a significant component in the supply portfolios of the major German electricity companies, next to end-customers and other suppliers. In some cases trading now makes up to 70 per cent of all sales (see bar chart).

Trading rose from relatively low levels in1998 to more than 300TWh in 2001. This makes trading perhaps an even more important driver for volume growth than mergers and acquisitions. However, some questions come to mind when looking deeper into these trading sales.

Companies typically class their trading sales as ‘physically delivered’. However, it is difficult to see where 300TWh of ‘physically delivered trading sales’ could go. The volume of the German physical trading exchanges is about 30TWh: And while there probably are international trades within the 300TWh as well, even Nordpool has only about 100TWh of physical volume.

Companies do not disclose what they mean by ‘physically delivered’, so one can only speculate about where all this volume goes and what it comprises.

What is easier to understand is how these trading sales are sourced. Electricity generation volumes have remained stable for the last few years, as have physical sales to end customers and other suppliers for most companies. Because trading sales are not generated or offset by reductions in other sales volumes, they must be purchased, either in bilateral negotiations, over-the-counter transactions or from physical exchanges.

Trading sales purchased from the wholesale market look pretty much like trading volume. Hence all companies try to back their trading sales figures with even bigger trading volumes, on average four times higher than sales. Again, there are no definitions of what constitutes ‘trading volume’. Since all the sales are purchased from the wholesale market, one can only speculate that some companies count 1MWh twice — once when it is purchased (a market trade) and once when it is sold (also a market trade).

What happens if a company trades the same product several times (for instance, buying and selling ‘baseload August 2004’ four times due to price developments) one can only guess.

There is no doubt that trading has an important role to play in a competitive market. When customers’ demand shape and volume can change significantly during one year but generation assets cannot, a company needs a good trading business to make ends meet. But as the proportion of trading is way beyond any risk management levels, one must question why sales volumes need to be so inflated. The answer is simple: size matters. A high sales figure signals market power. An electricity company with a large sales volume can brand itself as a heavyweight in the market. Indeed, many take headline sales figures seriously.

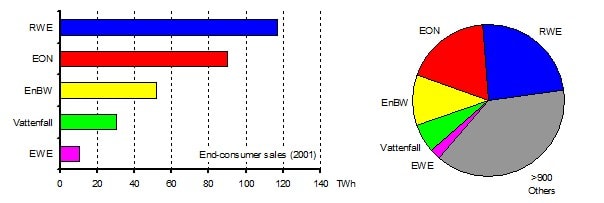

When VDEW (the German Electricity Association) last published its list of the largest German electricity suppliers, MVV was placed at number five. However, in terms of the number of customers supplied, there are eight suppliers in Germany in front of MVV (EWE and GEW Köln are about three times bigger). The VDEW list in itself reads strangely, because the combined market share of the ten largest German suppliers, if added up, comes to 140 per cent.

Analysts, too, typically use companies’ headline sales figures as their actual figures, and as a result one can sometimes find interesting market share estimates from them as well. However, when assessing a company’s performance, it is dangerous to treat trading sales the same as sales 10 end-customers or other suppliers.

There is no customer loyalty behind trading sales. Selling 1TWh in the wholesale market is easy compared with selling 1TWh in the end-customer market. The latter would require the addition of about 300,000 customers, and only a few suppliers have achieved that in the German market. The German competition authorities (the Bundeskartellamt) frequently emphasise the importance of end-customer markets in their decision documents on proposed takeovers in the German electricity market.

One reason so many people accept headline sales figures even though they include trading is that the real figures arc hard to come by. Since liberalisation in 1998, VDEW has not published end-customer sales figures. The electricity suppliers judged this information confidential and stopped giving the necessary data to VDEW. Most company reports provide a basic structure of the sales portfolio, but do not give a breakdown into national markets. So one has to dig deeply into published data to come up with figures for end-customer sales, and this facilitates only estimates. The pie chart provides an estimate of market shares in the German market.

Although the German market is fully liberalised, customers in the main are not switching. Even customers who have switched supplier show a high degree of loyalty. Yello, the mass market supply subsidiary of EnBW, raised prices significantly at the beginning of 2002 with hardly any customer losses. All of the large four German electricity suppliers are active in the nationwide supply market, if not necessarily in all segments.

However, organic growth is a difficult and slow process, especially in the German market with all its quirks from the lack of regulation. So the temptation is strong to inflate sales volume by trading. A strong trading outfit is definitely an indispensable prerequisite of a strong electricity company. But sales to the wholesale market of electricity sourced from the wholesale market do not make a reliable measure of Company size.

The sad conclusion is that most of the statistics that purport to describe the German electricity market are misleading. So what is needed? A first step would be to agree on some basic rules and regulations. Trading volumes are so difficult to value properly because there are no rules or definitions of trading sales. This regulation could be either self-regulation or imposed from outside, As the issue of size is close to the heart of electricity companies, some pressure from outside the industry might be needed to agree on standards.

As a second step, companies should reconsider whether providing basic information on sales really damages their competitive position. Arguably, there is even a public interest in these figures being available, at least on a rough basis. For example, accurate annual consumption figures are needed to inform considerations about security of supply. In the end it is in the interest of companies to give a true picture about their position in the electricity market.

The rules in Germany concerning how electricity statistics are compiled originate from the days when there was monopoly provision, and they need to be updated for competition, Until this happens, success stories built on trading should be taken with a pinch of salt, ‘physically delivered’, of course.

(Foto Jeffry Surianto)

Dr. Christoph Müller

www.linkedin.de/mueller-energieWeitere Artikel

Bleiben Sie auf dem Laufenden

Tragen Sie sich jetzt in meinen Newsletter ein, um benachrichtigt zu werden, wenn ein neuer Artikel erscheint.

Sie haben eine Frage oder ein spannendes Thema?

Kontaktieren Sie mich gerne per E-Mail.